Contact:

Case Studies

Here are some case studies where computer forensics played an important role.

Departed Employee Joins or Forms Competitor

We’ve dealt with dozens of matters involving departed employees who left to join or form a competitor, taking some or all of their prior employer’s confidential information with them. This story repeats itself again and again, but sometimes the facts are particularly egregious. In one notable matter, two employees left and immediately formed a competing venture in a highly technical industry. The client knew that these departed employees would have serious problems putting together a turnkey operation like this so quickly – especially one that was already showing up in the complicated industry bidding process - but it was having trouble identifying any specific wrongdoing that had occurred. A couple months later, another employee left the client and joined the new competitor. We performed a forensic analysis of that employee’s hard drive. As it turned out, the forensic evidence showed that the client employee had been working for, and shuttling confidential client materials over to, the new competitor before leaving. The employee had shared one of the client’s IP crown jewels and had even offered the competitor access to one of the client’s company servers. The forensic evidence also showed that this employee had been working on both sides of the same project bid, though it was clear that the client hadn’t been getting the same double-agent intelligence that the new competitor was getting. After some painful litigation, the new competitor paid a substantial sum to make the client whole.

Click here for more real-world egregious examples of “One or two guys walked off with our dog”

Violations of Protective Order

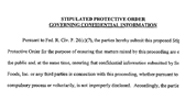

It’s not always business clients caught in the act by computer forensics. Attorneys often enter into court-approved agreements called “protective

orders” that are designed to do things such as protect privileged or confidential information and set up rules for the document discovery process. In one matter, the attorneys had agreed to a “claw-back” provision in their protective order that stipulated the attorneys would stop reading and immediately return any inadvertently produced privileged materials or media containing those materials. Our side discovered that some privileged materials were inadvertently produced and gave the other side notice pursuant to the protective order, requiring the other side to stop looking and immediately return the production hard drive. The other side took their time returning the production drive, so when it came back we performed a forensic analysis of the activity on the drive. We could tell that not only had the other side accessed hundreds of files, but it had also opened and viewed dozens of files after the protective order notice, in clear violation of the protective order terms. Even worse, some of the opened files were stored in locations indicating that they were likely to contain privileged material. The other side’s story quickly went from “We never violated the protective order – how dare you accuse us of that!” to “Aww shucks, maybe we did violate the protective order, but nobody got hurt.”

Employee Lawsuit Carefully Orchestrated From The Start

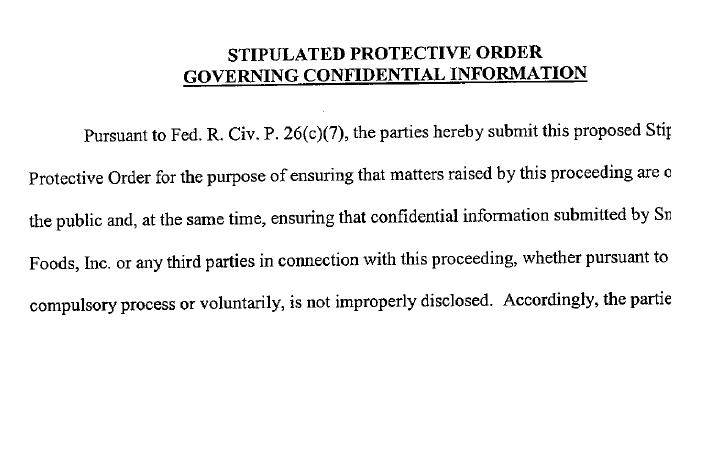

Sometimes employers break the law and are sued by employees for good cause. Sometimes employees sue their employers without merit, perhaps to act out a grudge or in hopes of a nice settlement payout.

In one case, the client (employer) was sued by an employee for what amounted to sexual harassment. The employee was quick to offer various forms of proof, mostly in the form of co-worker declarations and testimony. An examination of the employee’s work email seemed consistent with the proffered facts, but the alleged harasser did not agree with the version of the facts presented in the declarations produced by the complaining employee. A forensic analysis of the employee’s computer revealed back-channel communications between the complaining employee and the co-workers providing declarations and testimony. It turned out that the complaining employee had carefully planned out the lawsuit in advance, off the record, by conjuring many of the facts and getting co-workers to agree to declare to those facts using specific language provided by the complaining employee. Similar in some ways to the case of Rambus, Inc., v. Infineon Technologies AG, et. al., 220 F.R.D. 264 (E.D. Va., March 17, 2004), it did not help that the evidence had been carefully manipulated in advance of the lawsuit.